Few things can ruin a backpacking trip quicker than relentless swarms of buzzing mosquitoes. We’ve all been there – continuous swatting, itchy red welts, and early retreats to your tent.

Besides being annoying and irritating, mosquitoes can also be quite dangerous. Mosquito-borne illnesses kill more people worldwide — about a million a year — than any other predators combined. Scientists say that with continued disruptions in normal weather patterns, we can only expect this trend to get worse or more widespread.

That said, there’s no reason to let mosquitoes prevent you from getting outside. If you’re hiking during warm spring or summer nights, dealing with mosquitoes will most likely be inevitable, but there are some simple steps you can take to protect yourself and make your trip much more enjoyable.

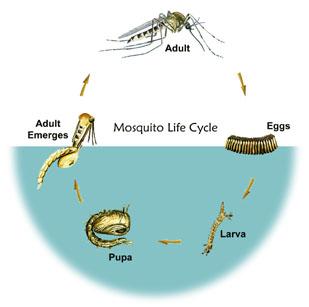

The Life Cycle Of A Mosquito

Although there are some variations between the more than 3,000 species of mosquitoes, they all follow a similar lifecycle. Like many insects and spiders, adult males aren’t the biters or blood feeders. That’s the role of the adult females. Once females get their blood meal from a mammalian host (humans and animals), they look for a water source and lay their eggs.

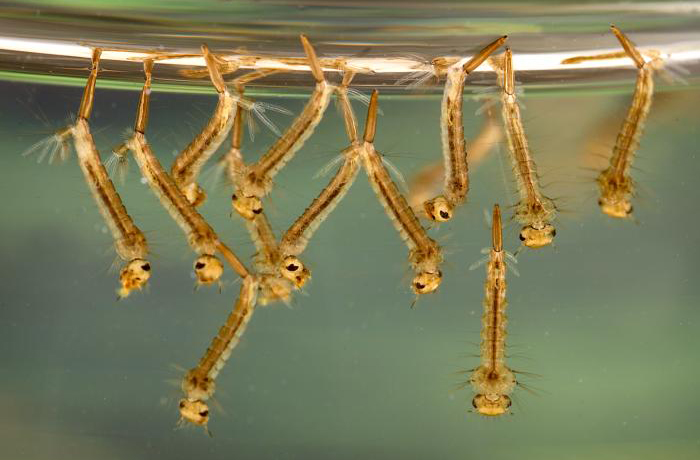

Larvae hatch from the eggs and “wiggle-propel” themselves to the water surface, hanging upside down using a “siphon tube” to feed on oxygen for 7 to 14 days before they shed their skin and become pupae. They take an extended rest period to develop, and then emerge from the pupae case, taking their time to dry out their antennae and wings and take flight. Most mosquito species grow from egg to adult in about 2 weeks.

After only two days as an adult, a female mosquito will bite its first host. Most male mosquitoes only live for two weeks. Female live up to a month or more. Some species don’t bite. Some feed instead on plant nectar, reptiles, or birds.

Species Of Mosquitos

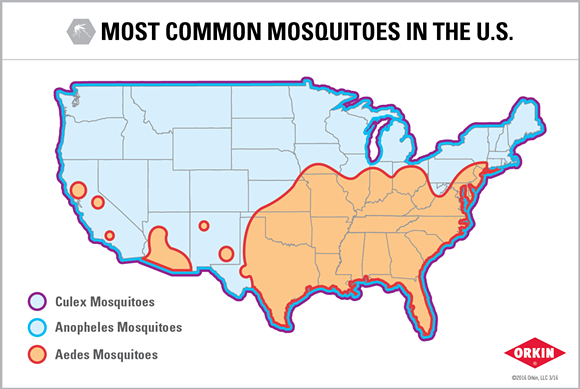

Although there are over 3,000 species of mosquitos worldwide, only three of them are responsible for making life miserable in our backyards and the backcountry.

Aedes

A species of Aedes (Aedes albopictus ) called the Asian Tiger mosquito hitched a ride into the U.S. in the 1980s in some imported automobile tires. Once inhabiting only the tropics, this mosquito is now found worldwide and is responsible for transmitting yellow fever, Dengue fever, chikungunya, canine heartworm, filariasis (elephantiasis) and West Nile virus. Aedes vexans is common throughout southern Canada and the U.S. (with the exception of Hawaii),mostly due to a wide range of habitats it utilizes. It’s has one of the meanest bites (fierce and painful) of all U.S. mosquitos.

Anopheles

Mostly found in temperate and tropical climates, this mosquito transmits the much-feared mosquito-borne disease malaria, which kills more than a million people worldwide each year. They typically incubate in clean water (instead of any water) and come out at dusk and stay active until dawn. They transmit diseases through saliva rather than just their bite.

Culex Pipens

Also known as the common house mosquito or Northern house mosquito, this species resides in urban and suburban areas across the globe, and transmit a number of viral infections, including Japanese encephalitis and West Nile Virus. Aggressive and persistence biters that leave a itchy and painful welt, they primarily bite early in the morning or later, from dusk until a few hours into the night.

Associated Diseases

Though many mosquito bites are innocuous, some can transmit a multitude of diseases to humans and animals, some extremely serious.Below is a list of associated diseases hikers will want to be concerned about here in the U.S.

West Nile Virus

The most common mosquito-borne illness in the U.S., more than 55,000 people have been infected since the disease first appeared here in 1999. Of them, many have experienced serious illness and some have even died according to the Centers for Disease Control. Since many cases go unreported, the CDC estimates that more than 3 million people, in every state except Alaska and Hawaii, have actually been infected. The virus is spread by mosquitoes that have bitten infected birds and then carry it to humans. It can causes fever, accompanied by body aches, disorientation, diarrhea, neck stiffness, headache, joint pain and tremors, and can also spread to the brain. Only about 1 percent develop potentially fatal encephalitis or meningitis.

Chikungunya

Spread by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, this disease is still pretty rare in the U.S. It’s characterized by the sudden onset of fever and severe joint pain, usually 3-7 days after being bitten by an infected mosquito. Other symptoms include headache, muscle pain, joint swelling and rash.

Dengue fever

Recently spread to the U.S. from Latin America and Asia, dengue fever has been reported in Texas, Florida and Hawaii. Four strains of the virus produce symptoms such as severe head aches, high fevers, and eye, bone, muscle and/or joint pain. Getting this virus puts you at risk for a potentially fatal dengue hemorrhagic fever should you get infected a second time.

Arboviral Encephalitis

Culex mosquitos spread various forms of this disease including St. Louis, Western Equine, LaCrosse, and Eastern Equine (EEE). All are endemic to the U.S. and increasing in incidence. The most common symptoms of the disease are flu-like with head and muscle aches, fever and nausea. In young children, the disease can be far more serious, including fatal.

Yellow Fever

A viral infection, symptoms can appear from a few days to a week later and include headache, backache, muscle ache, fever and chills. Around 15 % of people who get yellow fever develop serious illness that can lead to shock, bleeding, organ failure and, rarely, death.

Zika

Not life threatening and often only mildly symptomatic, this viral infection typically causes fever, rash, headache, joint pain, conjunctivitis and/or muscle pain lasting for several days to a week. People usually don’t get sick enough to go to the hospital, and they very rarely die of it. That said, the CDC reports that Zika can be passed from a pregnant woman to her fetus. Infection during pregnancy can cause certain birth defects.

The Bite: How & Why

Scientists at the CDC are eager to dispel the notion that blood type, foods we eat or the color of our clothing attract or repel mosquitos. Reports on those things have been refuted, apparently because of bad study statistics, or invalid methodology. What we do know, is that there are a variety of ways in which mosquitos do detect their hosts.

Movement

Mosquito’s eyes are highly sensitive to movement and they’re more likely to detect people who are moving around. This explains why they’ll often swarm hikers and backpackers on the trail.

Body Heat

Mosquitos can also detect body heat. People with higher body temperatures are at risk of increased targeting. If possible, try to stay cool and dry while you hike.

Bacteria On Skin

Scientists say we also advertise our presence to mosquitoes through scent signaling. Each of us carries an ecosystem of bacteria on the surface of our bodies, although it varies from human to human.

Chemical Scents

Further, we all have a unique chemical makeup that may or may not attract mosquito. Researchers say that in addition to bacteria, our skin exudes hundreds of these different chemical scents, including body odor, secretions and lactic acid (sweat). Sweating releases high concentrations of several combinations of body chemicals. Because of this, hikers and their sweaty gear ring the skeeter dinner bell.

Other compounds we excrete include ammonia, carbon dioxide, carboxylic acid (a fatty acid), and octenol (similar to lactic acid but found in the breath and scent of most mammals). Most mosquito species are equipped with sensory mechanism that detects and attracts them to these odors. This explains how mosquitoes are able to find their blood meal hosts, even in complete darkness.

Preventing Bites

As we mentioned above, mosquito bites are not only irritating but also potentially dangerous. Preventing bites and the potential transmission of diseases is essential. Below are some steps you can take to protect yourself.

Mosquito Repellents

One of the best ways you can protect yourself against mosquitoes is to apply an EPA-registered insect repellent on your skin and clothing when you go out. Repellents primarily work by masking the chemicals your body emits to thwart mosquitos on the hunt. Reapply these repellents often as they lose their efficacy with sweat, wear and water exposure. They typically come in sprays, lotions and creams, and include one or a combination of the following four active ingredients:

Deet: (N, N-diethyl-m-toluamide) – Available in a variety of strengths (effectiveness increases with concentration), studies show that concentrations of 30%-50% DEET are more than sufficient for most environments, and for teens and adults. DEET in 5 to 10% formulations are considered safe for children over 2 years of age. Spray is the safest way to apply DEET; avoid getting it on hands or wash thoroughly after using lotion. Also, DEET should only be used on exposed skin; applying it to clothing or gear can dissolve certain materials.

Permethrin: Buy factory treated clothing with permethrin or treat the outside of your clothing and gear with a permethrin. Although technically an insecticide, this repellant kills mosquitoes. It won’t keep mosquitoes from landing on you (like DEET or Picaridin) but rather incapacitates and eventually kills mosquitos after they land on you. Avoid spraying on skin (human or pet) as it can have toxic effects and is hard on skin. Apply instead to your clothing and boots and make sure you use enough as too light a coating will wear off quickly.

Picardin: Unlike DEET, Picaridin is fairly low on odor while still being equally effective. It won’t irritate skin or damage synthetic fabrics or plastics and claims to be effective for up to 8 hours.

IR-3535: This ingredient has just recently been approved for use in the U.S. but has been widely used in Europe for years. IR-3535 helps repel mosquitos, ticks and biting flies with lower toxicity than DEET. It’s safe to use on infants, pregnant and breastfeeding women.

Other Prevention Tips

Thermacell Mosquito Repeller: A more recent addition to the repellent game, the Thermacell Backpacker Mosquito Repeller has gotten rave reviews. Using heat generated from your stove fuel canister, it disperses a repellent to create a 15 foot protection zone. It doesn’t emit an odor and does not contain DEET. We’re excited to do further testing this summer.

Avoid fragrant soaps and toiletries: Avoid using fragrance-infused soaps and toiletries. Use of these will leave microscopic scents on your skin, which will attract mosquitoes.

Wear long sleeve shirts and pants: The more skin you expose, the more vulnerable you’ll be to mosquito bites, so long-sleeved shirts, long pants and socks will help protect you. Tight weaves of polyblend are a lot more effective than light weight cotton or even newer generation lightweight wool.

Protect yourself at peak times: Peak feeding times for mosquitoes are at sunset and sunrise, so either avoid going out then or be extra careful to take precautions against being bitten.

Wear a mosquito net hat: Head nets with insect shields will keep skeeters, gnats, and deer flies away from your face and neck. The nets in mosquito hats contain holes small enough to let air through yet block mosquitos from entering. The key is to keep an air barrier between skin and the net. Don’t let it lay on your skin, as mosquitos can still bite through given time and opportunity.

Choose rest sties & campsites carefully: Avoid mosquitos by avoiding places where they breed and incubate, such as damp, low-lying places. Place tents at least 100 yards away from water sources. Mosquitos don’t do well in hot, dry and sunny locales so setting up your tent in a sunny area can also help.

Natural Approaches

A number of different all-natural substances are available that help repel mosquitos. They can be a good option for those looking to avoid harsh chemicals or for children. A wide variety of brands are available, but here’s the ingredients (usually in combination) you’ll want to consider:

Citronella: Citronella is derived from a type of grass and is generally regarded as safe when used correctly. Citronella has a lemon-line-lemongrass scent to it and it comes in candles, sprays, lotions and bracelets.

Oil of lemon eucalyptus: ( p-Mentane-3,8-diol) – Oil of Lemon Eucalyptus has been deemed as effective as a 10% to 20% DEET solution (similar to citronella) and has been approved for children older than 3 and adults. It has a synthetically produced eucalyptus leaf scent (not to be confused with lemon eucalyptus essential oil).

Catnip oil: Most cat owners known the catnip herb (containing the chemical compound Nepetalactone) as “kitty cannabis.” But Catnip Oil is a potent mosquito and fly repellent. Researchers report that it’s about 10 times as effective as DEET at repelling mosquitos.

Essential oils: Lemon, thyme, peppermint, eucalyptus, basil, clove, lemongrass, geranium, tea treeand lavender, in a combination of three or four, definitely provide a fairly effective repellant. Make your own lotion or spray or ointment. Essential oil repellents are believed to be effective anywhere from 30 minutes to 2 hours.

Environmental Considerations

It’s important to keep in mind that as much as we despise them, mosquitos, like ticks, are part of a complex food web. Many fish feed on mosquito larvae, while birds and spiders and other insects, like dragonflies and damselflies, feed on the adult mosquito. Frogs also are highly dependent on adult mosquitoes as a food source, while tadpoles eat the larvae.

Some prevention approaches have serious environmental impacts. There’s some steps you can take to help protect the ecosystem. Never swim in a lake or stream with a coating of synthetic or natural repellants or insecticides on your body. Wet your pack towel and wipe your body down to remove as much residue as you can. You can also take a water bottle shower to wash off contaminants, making sure you are at least 200 feet from any water source. DEET, picaridin and permethrin are toxic to fish and other invertebrates that live in either salt water or fresh water.

Conclusion

Although mosquitos can be quite irritating in the backcountry, they should not prevent you from spending time outdoors. Equipping yourself with the strategies and tips listed above will make your trip far more enjoyable and safe.

We hope this guide helps prepare you for backpacking and hiking when mosquitoes are present.